I honestly did not think The Scarlet Letter was that bad. I know — shocking opinion from someone who survived a junior year English class. Although the less contemporary stylings of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s writing made the book a less intuitive read than others, I still had a fun time with it. I enjoyed watching the narrative unfold: the cast of unique characters changing, and their fates intertwining.

Though many high school students, especially ones here at Masuk, had trouble finding the same enjoyment I did, it is clear that at least someone likes it. If no one liked it, or even if most readers disliked it, The Scarlet Letter would have never been taught in schools. It would have never carved out its own place in our country’s literary canon. If The Scarlet Letter was really a crappy book, we probably would have never heard of it in the first place.

A common mistake that bugs me to no end, when it comes to critical discussion of media, is confusing an assessment of a work’s quality with your own subjective opinion of the work. Or, in simpler terms, The Scarlet Letter is a well-crafted book; you probably just don’t like it. There is, or at least always should be, a clear difference in your mind between your personal opinion of a work of art and an objective evaluation of it.

I repeatedly mention Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter because I feel that this book in particular has been unjustly wronged by the people of this school again and again. Last year, before my English class had even touched the book, I heard gruesome accounts of the horrors of The Scarlet Letter from students who had already read it.

“It sucks. I didn’t like the characters. They’re lowkey kinda bland,” said senior Nazar Dudko. “The symbolism of The Scarlet Letter honestly doesn’t make sense”

So when it came time for me to venture into the world of 17th-century Massachuesetts, I was expecting the worst. Just for it to be… kind of pleasant. Sure, I recognize that Hawthorne loved droning on with words that sound half-made-up, crafting imagery that seems very loosely relevant, if relevant at all, to the actual events taking place. But I also recognize that despite some flaws, the book was certainly written well.

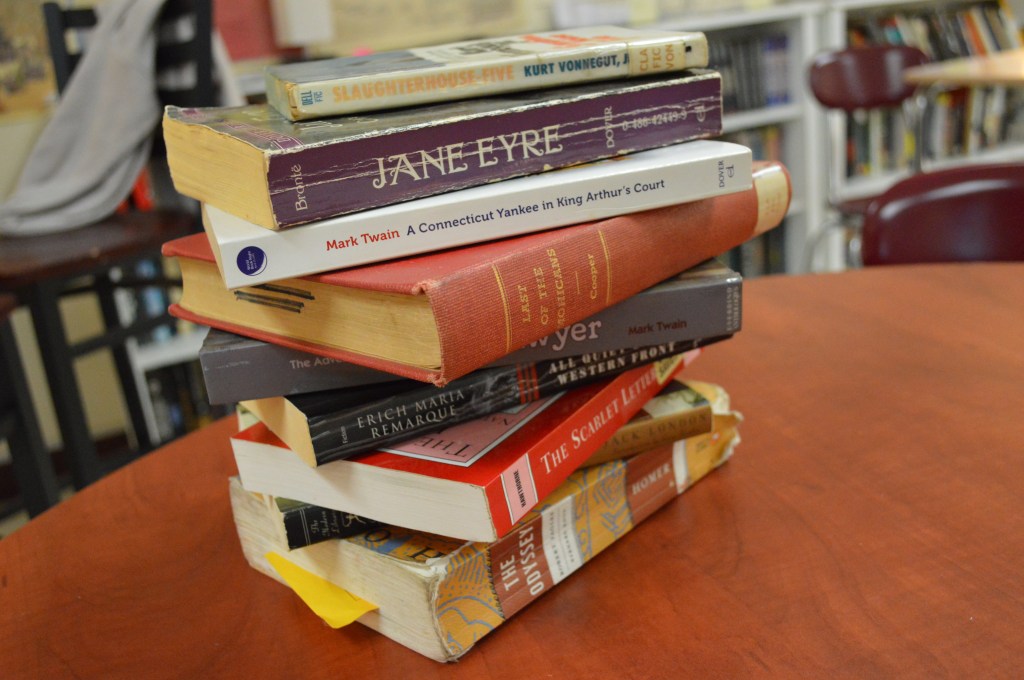

And I’d expect nothing less. Do you think the books that we are given in school are just chosen at random? There are multiple levels of oversight to ensure that we are given “good” books. A teacher must first present the book to the English instructional leader, before a curriculum council reviews the book. This ensures that, amongst other things, it is of a high enough quality to be taught. The books you read in school are not random; multiple people deem that they’re worth reading.

“The story is stupid. Why does he just die like that?”

The book has depth. There are intentional, sub-contextual meanings behind nearly every plot event: symbolism; figurative language, broad, almost universal themes that nearly everyone can relate to in some way. All qualities that are indicative of a well written narrative. Hester, Dimmesdale, and Chillingworth, and all of their actions are all intricate messages to the reader.

“It’s soooo hard to read. The words don’t make any sense!”

Though sometimes (more like oftentimes) the diction and sentence structures that Hawthorne selected can make for a more challenging read, these choices were made very deliberately. Every use of unique diction and complex syntax is a testament to Hawthorne’s attention to detail when writing. However complex of a storyline these intentional choices create, they work towards best illustrating the world that Hawthorne was trying to form. Which brings me back to my main point: regardless of smaller criticisms, I find it impossible to classify The Scarlet Letter as a badly written book when it has so many clear merits.

But enough about The Scarlet Letter. This principle can and should be applied to all media that we critique. A piece of art can be well made while still being something that you don’t like.

A piece of art can be well made while still being something that you don’t like.

And on the flip side, a work can mean the world to you, yet objectively not be perfect. Our preferences are built upon our own personal experiences in the world — the trillions of minute variables that make up our perspective.

One of my favorite movies of all time is Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man. Though more than two decades old, I find the campy dialogue and humor ever charming. In between the comedic moments, the heartfelt coming-of-age narrative still inspires me. The movie also brings me back to when I was a little kid, seeing Spider-Man swing through the New York skyline for the first time. Acknowledging all of that, is Spider-Man the best film I’ve ever seen? I’d say no.

I understand the criticisms of the cast. Tobey Maguire was far from the perfect actor to play a teenage boy. The supporting cast leaves a lot to desire as well, with Spider-Man’s friends serving more as plot devices than actual characters. The visual effects have not only aged poorly, but even look bad compared to other movies of the era. Though it is a fun watch, I wouldn’t consider the greater narrative of the movie to be groundbreaking or exceptional in any way. All-in-all, Spider-Man is no Interstellar or Pulp Fiction.

We all should have a clear separation in our minds between our own subjective opinion of a work and the logical side of our mind being used to assess the “goodness” of the art. But that begs the question, is there any level of objectivity when critiquing art? Some may argue that art is purely subjective. That there is no such thing as an objective quantification of how good art is. I think that “some” must have skipped elementary school art class, or any art class for that matter. An art teacher does not just grade their students based on how much they “like” their work. There are layers of technique, sophistication and composition that go into a work of art, and all of that can be judged in a non-arbitrary way.

Critics exist for a reason. Whether they’re film critics or food critics or literally any other type of critic, they set a level of standards for art. In a world where objective critiques of art didn’t exist, there would be no such thing as good writing, good sculpting, good direction. So ultimately, maybe The Scarlet Letter isn’t an egregious piece of literature. I’m tired of having to defend a book that has outlived generations. It takes a metric butt-load of arrogance to proclaim, as a teenager, that a work that has been deeply analyzed by hundreds if not thousands of literary scholars is of poor quality simply because you didn’t like it.

You’re not a master media analyzer, you’re in high school. Go do your homework.

Leave a comment